For all you AoD readers in the Tampa Bay area: pick up a copy of the St. Petersburg Times this afternoon. The Thing I Carried is in the feature section, likely buried somewhere near the back. And if you're wondering what I have to do with Florida, well, me too buddy. If you want to contribute to the death of newspapers (or simply don't live in America's Wang), you can read the full article here.

AH

Sunday, October 26, 2008

Sunday, October 19, 2008

And now, an important message

I received a bit of feedback from my post about the feelings of coming home from a deployment, but a couple of emails asked for advice on the flip side of that coin - how to deal with a returning soldier. I've never set foot in an FRG meeting so I'm not familiar with the concerns and worries of wives and girlfriends of a deployed soldier. In any case, I hope this benefits the kind women who inquired and those out there that have unanswered questions gnawing away at them. Following are questions sent by women who have a romantic link to a deployed soldier, answered here not just for their benefit but for everyone in the same predicament.

How often do soldiers want to receive letters? (especially if you have rare access to internet/phone.)

Ideally, what do you want to hear from your friends?

This is a tough one. All my loser friends from home couldn't be relied upon to send an occasional e-mail while I was deployed. My only friends were to the left and right of me in Iraq. But if you're a better friend than what I had, let them know what you have planned for their return. If it's a party, a get-together with other friends, a getaway to a favorite spot, whatever. It provides something to look forward to, a familar setting for a place that will seem a world of difference when the soldier returns. A year, fifteen months, however long the deployment is - a lot has changed in society. Familiarity is key to reintegration. When I left, the coolest thing cell phones did was flip open. When I came back, phones had keyboards. It was incredible, strange and confusing all at the same time.

Be sure to keep them up to date with news. Toward the end of my deployment, we spent anywhere from 3-10 days in the urban wilderness of Baqubah. When we came back to the base, sweaty, filthy and exhausted, the only news we caught was at the dining facility, which was permanently set on Fox News. I could only rely on Bill O'Reilly and Fox & Friends for news, which is like relying on a prostitute to give you safe-sex tips. Let them know what's going on in the world using whatever means you like - phone, emails or letters.

What do you NOT want to hear from your friends?

Don't ask obtuse questions like "how hot is it?" and "did you kill anybody?" It's offensive and flippant. Let them know how things are going in your life, but don't approach it as something they're "missing." They know. Don't press the issue.

What can a friend do to bring her soldier out of his darkness, besides consistent messages of support and willingness to listen or just sit with him?

How often do soldiers want to receive letters? (especially if you have rare access to internet/phone.)

The answer is simple: all the time, especially if contact by phone and internet is limited. Forget mp3 players, DVDs and X Box 360s- letters from home, and especially from a woman, provide the ultimate comfort and peace of mind to a soldier in a war zone. No matter how long a deployment feels, they're ultimately finite. The link back home must remain strong to keep a soldier's head level, and writing letters to them is instrumental. When a young lady named Lauren was writing to me, I treasured every letter sent, reading them over and over. They came with me everywhere. As long as there has been war, there have been letters sent from home to the men fighting as a delicate reminder of what was left behind.

Ideally, what do you want to hear from your friends?

This is a tough one. All my loser friends from home couldn't be relied upon to send an occasional e-mail while I was deployed. My only friends were to the left and right of me in Iraq. But if you're a better friend than what I had, let them know what you have planned for their return. If it's a party, a get-together with other friends, a getaway to a favorite spot, whatever. It provides something to look forward to, a familar setting for a place that will seem a world of difference when the soldier returns. A year, fifteen months, however long the deployment is - a lot has changed in society. Familiarity is key to reintegration. When I left, the coolest thing cell phones did was flip open. When I came back, phones had keyboards. It was incredible, strange and confusing all at the same time.

Be sure to keep them up to date with news. Toward the end of my deployment, we spent anywhere from 3-10 days in the urban wilderness of Baqubah. When we came back to the base, sweaty, filthy and exhausted, the only news we caught was at the dining facility, which was permanently set on Fox News. I could only rely on Bill O'Reilly and Fox & Friends for news, which is like relying on a prostitute to give you safe-sex tips. Let them know what's going on in the world using whatever means you like - phone, emails or letters.

What do you NOT want to hear from your friends?

Don't ask obtuse questions like "how hot is it?" and "did you kill anybody?" It's offensive and flippant. Let them know how things are going in your life, but don't approach it as something they're "missing." They know. Don't press the issue.

What can a friend do to bring her soldier out of his darkness, besides consistent messages of support and willingness to listen or just sit with him?

Let them decide when to open up. It's not something to coerce out of him. He knows you'll listen intently with empathy and support. That's not the issue. The issue is him being comfortable enough with what he has seen and done to talk about it openly. It takes time, and unfortunately everyone is different regarding this issue. War does not leave anyone untouched, physically or mentally. Something about him will change. Your best bet is to recognize that and do your best to understand why the change happened. It could take six months or six years for him to come out of his shell. Be patient.

From another inquirer:

Is him wanting to be alone to decompress and adjust normal for someone coming home from war, even when you have loved ones who want to be with you?

This is a position of extremes. A soldier will either want to be surrounded by loved ones immediately, or he'll want to be alone to sort out his feelings. Everyone is different, so there's no real solution to this if he wants to do something contrary to your wishes. He knows what's best for him to do, so go along with it. Just be sure he doesn't get on that slippery slope of alcohol abuse. It happens like clockwork to returning units, and the first line of defense is other soldiers and loved ones. Keep an eye on him but don't be intrusive.

Hopefully this provides at least a shred of insight for those looking for answers during trying times. If you want answers to your own questions, either leave a comment or email me at hortonhearsit at hotmail dot com.

Also, this is my 100th post. Thanks for keeping up with me dear readers. It has been rewarding beyond belief to stick around this long.

AH

From another inquirer:

Is him wanting to be alone to decompress and adjust normal for someone coming home from war, even when you have loved ones who want to be with you?

This is a position of extremes. A soldier will either want to be surrounded by loved ones immediately, or he'll want to be alone to sort out his feelings. Everyone is different, so there's no real solution to this if he wants to do something contrary to your wishes. He knows what's best for him to do, so go along with it. Just be sure he doesn't get on that slippery slope of alcohol abuse. It happens like clockwork to returning units, and the first line of defense is other soldiers and loved ones. Keep an eye on him but don't be intrusive.

Hopefully this provides at least a shred of insight for those looking for answers during trying times. If you want answers to your own questions, either leave a comment or email me at hortonhearsit at hotmail dot com.

Also, this is my 100th post. Thanks for keeping up with me dear readers. It has been rewarding beyond belief to stick around this long.

AH

Sunday, October 05, 2008

The Thing I Carried

Out of the Army and into school. That was the simple two step plan that many of us adopted before we deployed in the summer of 2006. Nearly half of my platoon would be getting out if and when we made it back home from Iraq. We focused the best we could when it came to preparing for the mission, but there is no helping the excitement in the prospect of starting a new chapter of life on the government's dime.

In the run-up to the deployment, a lot of guys were buying their own equipment to take with them. It is generally accepted that government issued equipment is inferior to what you can go out and buy yourself. The assault pack was one of those things. It's just like a backpack except with a sweetass name. The only problem was the zipper sucked something fierce and it held no more than what a high school backpack could carry. I'm the kind of person to carry backups of everything. Extra knives, batteries, carabiners, socks. I needed to haul a lot more than what the issue assault pack could carry.

Jesse hooked our whole squad up with aftermarket equipment. His dad's company sponsored us with thousands of dollars to buy magazine and utility pouches, vests and other luxuries. Jesse budgeted himself enough to buy a new civilian assault pack. He didn't need his old one, so he gave it to me.

"You can use it for the deployment, but you have to give it back to me," he said. "But if you decide to reenlist, you can keep it."

"You'll definitely be getting it back," I replied.

In the run-up to the deployment, a lot of guys were buying their own equipment to take with them. It is generally accepted that government issued equipment is inferior to what you can go out and buy yourself. The assault pack was one of those things. It's just like a backpack except with a sweetass name. The only problem was the zipper sucked something fierce and it held no more than what a high school backpack could carry. I'm the kind of person to carry backups of everything. Extra knives, batteries, carabiners, socks. I needed to haul a lot more than what the issue assault pack could carry.

Jesse hooked our whole squad up with aftermarket equipment. His dad's company sponsored us with thousands of dollars to buy magazine and utility pouches, vests and other luxuries. Jesse budgeted himself enough to buy a new civilian assault pack. He didn't need his old one, so he gave it to me.

"You can use it for the deployment, but you have to give it back to me," he said. "But if you decide to reenlist, you can keep it."

"You'll definitely be getting it back," I replied.

I made the secondhand assault pack my own. It was worn out after one deployment but still held together fairly well. The bottom corner was tearing. Jesse had written his Hawaiian name, Keawe, in thick, black lettering on the front. I sewed on a nametape to cover it up. I wrote in small print 24 Nov 2007, the day I was getting out of the Army. It was below a message Jesse had written - For those who would NOT serve

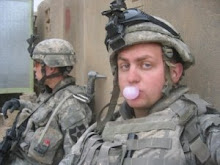

In Baghdad, I carried my assault pack everywhere we went. It was becoming a routine to leave our base in Taji and spend up to a week in smaller bases in the heart of the city. We began to live out of our assault packs, bringing whatever we could stuff in there. Mp3 players, books, movies, chess sets, snacks. I carried all of Lauren's letters with me so I could read them over and over. The rain had stained the notebook paper blue and red.

Jesse was always asking me when I was going to get a girlfriend. On the day I was going on leave, Josh told him I had a girl writing to me in Seattle. While my platoon went out to check out insurgents loading weapons into a car, I stayed behind and told Jesse the unlikely story of our relationship. "Damn dude, good luck with that shit," he said.

Two weeks later, Jesse would be cut down by small-arms fire in Baqubah. He would survive some time before passing away. I could not possibly avenge him; I was two thousand miles away. I heard about his death in the most undignified way; a Myspace bulletin read in an internet cafe in Rome.

In Baghdad, I carried my assault pack everywhere we went. It was becoming a routine to leave our base in Taji and spend up to a week in smaller bases in the heart of the city. We began to live out of our assault packs, bringing whatever we could stuff in there. Mp3 players, books, movies, chess sets, snacks. I carried all of Lauren's letters with me so I could read them over and over. The rain had stained the notebook paper blue and red.

Jesse was always asking me when I was going to get a girlfriend. On the day I was going on leave, Josh told him I had a girl writing to me in Seattle. While my platoon went out to check out insurgents loading weapons into a car, I stayed behind and told Jesse the unlikely story of our relationship. "Damn dude, good luck with that shit," he said.

Two weeks later, Jesse would be cut down by small-arms fire in Baqubah. He would survive some time before passing away. I could not possibly avenge him; I was two thousand miles away. I heard about his death in the most undignified way; a Myspace bulletin read in an internet cafe in Rome.

Coming back to Iraq after leave, I looked at Jesse's assault pack a lot differently. I still carried it with me everywhere, but I treated it a lot better. I no longer tossed it off the Stryker into the dust. I didn't shove it into small spaces on top of the vehicle. In the outposts where we lived, I used it as a pillow.

The assault pack is not an assault pack anymore. It's a backpack. I no longer stuff it with extra grenades, ammunition magazines or packages of Kool Aid. It now carries textbooks, calculators and pencils. I started my first classes a few months ago to fulfill the plan two years in the making. I imagined it to be a seamless transition into civilian life. Boy, I was fucking naive, even when I came home. I saw some guys falling apart from PTSD, getting drunk or doing drugs to drown it out. I thought I made it out okay, relatively.

With my unassuming tan backpack at my feet, I break out in a sweat if I even think about mentioning Iraq in the classroom. I let it slide nearly every time, yielding the topic to daftly opinionated classmates. I feel like a foreign exchange student, confused about the motivation of my peers. I literally carry the burden of readjustment on my back, not wanting to let go my past but anxious to get to the future. Fractured into part war veteran and part journalism student, who I am speaking to determines which part of me is actually there in the room. To many, my past is my best kept secret. For all they know, my parents pay my tuition and do my laundry. I can be honest here. It's terrifying to be honest out there. Perhaps it's best that way.

For those who would NOT serve - it's faded now, not easily read unless you look closely. I secretly wish that another veteran will read it, see the dangling 550 cord hanging from one of the buckles and ask, "what unit were you in?" At least then I could be myself with someone that carries the same load on their shoulders.

AH

The assault pack is not an assault pack anymore. It's a backpack. I no longer stuff it with extra grenades, ammunition magazines or packages of Kool Aid. It now carries textbooks, calculators and pencils. I started my first classes a few months ago to fulfill the plan two years in the making. I imagined it to be a seamless transition into civilian life. Boy, I was fucking naive, even when I came home. I saw some guys falling apart from PTSD, getting drunk or doing drugs to drown it out. I thought I made it out okay, relatively.

With my unassuming tan backpack at my feet, I break out in a sweat if I even think about mentioning Iraq in the classroom. I let it slide nearly every time, yielding the topic to daftly opinionated classmates. I feel like a foreign exchange student, confused about the motivation of my peers. I literally carry the burden of readjustment on my back, not wanting to let go my past but anxious to get to the future. Fractured into part war veteran and part journalism student, who I am speaking to determines which part of me is actually there in the room. To many, my past is my best kept secret. For all they know, my parents pay my tuition and do my laundry. I can be honest here. It's terrifying to be honest out there. Perhaps it's best that way.

For those who would NOT serve - it's faded now, not easily read unless you look closely. I secretly wish that another veteran will read it, see the dangling 550 cord hanging from one of the buckles and ask, "what unit were you in?" At least then I could be myself with someone that carries the same load on their shoulders.

AH

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)