“Hey man, just so you know, I’m going to set this thing off.”

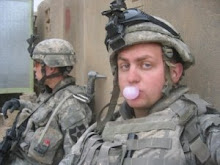

I don’t have a metal plate in my head or shrapnel in my legs, but I carry with me something that might as well be lodged deep under my skin. After Vietnam, soldiers and civilians alike would wear bracelets etched with the names of prisoners of war so their memory would live on even if they never came home. Veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan continued the practice, but with a twist. The same bracelets are adorned with the names of friends killed in action. The date and the place are also included as a testament to where they took their last steps. One of the first things my platoon did after coming home was order memorial bracelets from the few websites that specialize in military memorabilia. You don’t even have to type in the name or the date; their system uses the DOD casualty list. All you have to do is filter by name and a software aided laser will burn the selection onto an aluminum or steel bracelet. What emerges out of this casual and disinterested practice is jewelry teeming with the amount of love and commitment found in ten wedding rings.

Every trip to the airport has the same outcome: additional security checks and a pat down from a TSA agent. I tell them it’s the bracelet that the metal detector shrieks at. “Can you take it off?” is always the question. “I don’t want to take it off” is always the answer. To some screeners my answer is a poke in the eye of their authority, a wrench in the system of their daily routine. Others recognize the bracelet and give me a gentle nod and a quick pat down. I suspect they have encountered other veterans like me and realize the futility of asking to have it removed. In a glass booth at the security gate is where I most often get the question, “Who’s on the bracelet?” Those who realize the significance of it usually want to know the name. I stare down and rub my fingers over the lettering. “Brian Chevalier, but we called him Chevy.”

At times the memorial bracelets seem almost redundant. The names of the fallen are written on steel and skin, but are they not also carved into the hearts of men? Are the faces of the valiant not emblazoned in the memories of those who called them brothers? No amount of ink or steel can be used to represent what those days signify. My bracelet says “14 March 2007,” but it does not describe the blazing heat that day, or the smell of open sewers trampled underfoot or the sight of a Stryker, overturned and smoke-filled as the school adjacent exploded under tremendous fire. It was as if God chose to end the world within one city block. When Chevy was lovingly placed into a body bag under exploding RPGs and machine gun tracers, worlds ended. Others began.

The concept of Memorial Day nearly approaches superfluous ritual to some veterans. It's absurd to ask a combat veteran to take out a single day to remember those fell in battle, as if the other 364 days were not marked by their memories in one way or another. I try to look at pictures of my friends, both alive and dead, at least once a day to remember their smiles or the way they wore their kits. I talk to them online and send emails and texts and on rare occasions, visit them in person. We drink and laugh and recall the old days and tell the same war stories everyone has heard a thousand times but still manage to produce streams of furious laughter. I get the same feeling with them; Memorial Day does not begin or end on a single day. It ebbs and flows in torrents of memory, sometimes to a crippling degree. Most of us have become talented at hiding our service and safeguard the moments when we become awash in memories like March 14. The bracelet is the only physical reminder of the tide we find ourselves in.

Perhaps it's best to let civilians hold onto Memorial Day and hope they use the time to reflect wisely. A time to remember old friends or distant relatives that they did not necessarily serve with but still honor their sacrifice. Not just soldiers are touched by war. Chevy was a father and a son, and his loss not only rippled through the platoon and company but a small town in Georgia. The day serves as a reminder that there are men and women who have only come back as memories. Maybe the reflection on those who did not return is a key to helping civilians bridge the gap with veterans. Occasionally my bracelet spurs conversations with friends and coworkers who did not know I was in the Army or deployed to Iraq. I still don't feel completely comfortable answering their questions but I'm always happy to talk about the name on my wrist. His name was Brian Chevalier, but we called him Chevy.

I don’t have a metal plate in my head or shrapnel in my legs, but I carry with me something that might as well be lodged deep under my skin. After Vietnam, soldiers and civilians alike would wear bracelets etched with the names of prisoners of war so their memory would live on even if they never came home. Veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan continued the practice, but with a twist. The same bracelets are adorned with the names of friends killed in action. The date and the place are also included as a testament to where they took their last steps. One of the first things my platoon did after coming home was order memorial bracelets from the few websites that specialize in military memorabilia. You don’t even have to type in the name or the date; their system uses the DOD casualty list. All you have to do is filter by name and a software aided laser will burn the selection onto an aluminum or steel bracelet. What emerges out of this casual and disinterested practice is jewelry teeming with the amount of love and commitment found in ten wedding rings.

Every trip to the airport has the same outcome: additional security checks and a pat down from a TSA agent. I tell them it’s the bracelet that the metal detector shrieks at. “Can you take it off?” is always the question. “I don’t want to take it off” is always the answer. To some screeners my answer is a poke in the eye of their authority, a wrench in the system of their daily routine. Others recognize the bracelet and give me a gentle nod and a quick pat down. I suspect they have encountered other veterans like me and realize the futility of asking to have it removed. In a glass booth at the security gate is where I most often get the question, “Who’s on the bracelet?” Those who realize the significance of it usually want to know the name. I stare down and rub my fingers over the lettering. “Brian Chevalier, but we called him Chevy.”

At times the memorial bracelets seem almost redundant. The names of the fallen are written on steel and skin, but are they not also carved into the hearts of men? Are the faces of the valiant not emblazoned in the memories of those who called them brothers? No amount of ink or steel can be used to represent what those days signify. My bracelet says “14 March 2007,” but it does not describe the blazing heat that day, or the smell of open sewers trampled underfoot or the sight of a Stryker, overturned and smoke-filled as the school adjacent exploded under tremendous fire. It was as if God chose to end the world within one city block. When Chevy was lovingly placed into a body bag under exploding RPGs and machine gun tracers, worlds ended. Others began.

The concept of Memorial Day nearly approaches superfluous ritual to some veterans. It's absurd to ask a combat veteran to take out a single day to remember those fell in battle, as if the other 364 days were not marked by their memories in one way or another. I try to look at pictures of my friends, both alive and dead, at least once a day to remember their smiles or the way they wore their kits. I talk to them online and send emails and texts and on rare occasions, visit them in person. We drink and laugh and recall the old days and tell the same war stories everyone has heard a thousand times but still manage to produce streams of furious laughter. I get the same feeling with them; Memorial Day does not begin or end on a single day. It ebbs and flows in torrents of memory, sometimes to a crippling degree. Most of us have become talented at hiding our service and safeguard the moments when we become awash in memories like March 14. The bracelet is the only physical reminder of the tide we find ourselves in.

Perhaps it's best to let civilians hold onto Memorial Day and hope they use the time to reflect wisely. A time to remember old friends or distant relatives that they did not necessarily serve with but still honor their sacrifice. Not just soldiers are touched by war. Chevy was a father and a son, and his loss not only rippled through the platoon and company but a small town in Georgia. The day serves as a reminder that there are men and women who have only come back as memories. Maybe the reflection on those who did not return is a key to helping civilians bridge the gap with veterans. Occasionally my bracelet spurs conversations with friends and coworkers who did not know I was in the Army or deployed to Iraq. I still don't feel completely comfortable answering their questions but I'm always happy to talk about the name on my wrist. His name was Brian Chevalier, but we called him Chevy.