As the steady flow of commuters emptied out of the subway, I stood to the side, watching down avenues of approach with my head on a swivel. Jesse’s assault pack dug into my shoulders, heavy not from grenades or textbooks, but from enough clothes for a long weekend. I decided on a whim to take a long bus ride from Washington, DC to New York for Comic-Con. Dodo had gone last year and it seemed a perfect reason to visit him in Brooklyn. It had only been a few months since he came down to Washington, but I had missed him terribly. He remains one of my closest friends from our old platoon, and seeing him released the nostalgic pressure that builds in between visits with guys from the unit.

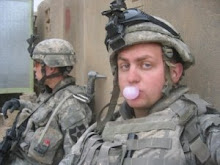

Peculiar things happen when you catch up with a guy from the platoon. Voices change, conversation becomes hurried and the wall between thoughts and speech, usually reserved for polite society, crumbles to dust. The social experiment of a platoon stuffed together for fifteen continuous months of combat breeds words, phrases and nicknames that are buried when those men finally disperse, only to be resurrected later during brief reunions. If the men of second platoon spoke as they did in the filthy outposts of Baqubah, most would be divorced and none would be employed. Reintegrating into society means you must leave those words, phrases and tones behind, mostly for the reason that civilians would simply not understand them. When old friends get together, those words come tumbling out from the deepest recesses of the mind.

When civilians ask me what I miss most about the Army, I always tell them it’s the people. Many are one of a kind and others are destined to be friends for life. Given a few years separation between the end of a military career and the return to civilian life, it becomes easy to romanticize the way things used to be. Even sheer moments of terror and unimaginable brutality seem tolerable in retrospect because of the men to the left and right. Love is a difficult emotion to conceptualize, and I did not understand it until I saw guys sharing their last swallows of water or offering to carry some of the heavy load for a struggling friend. Once we got home and everyone went their separate ways, or stayed for another tour, that support system fell apart. It was worth the agony of war to experience that kind of commitment.

It came as no surprise to hear that the Chilean miners almost immediately began to have what I call adversity withdrawal. In the two months they were underground, everything in their lives – their wives and girlfriends, their homes, their paychecks- melted away the moment they were trapped. Their only concern was survival, and they began to live moment to moment with an outcome far from certain. Undoubtedly, the bonds they forged deep underground helped them get through what must have been a truly horrifying experience. One sentence from a recent report nearly knocked me out of my seat:

“What we’re seeing is the miners are almost longing to be in that group together.”

For the third time this year, I spent quality time with Dodo, one of my best friends from the platoon. We always talk about work and girlfriends and who is up to what, but the topic always drifts towards the Army and Iraq, as if the conversation is a compass that points to what is really on our minds. I have discovered that several guys from the platoon have thought about joining up again. Going back to a job or the unemployment line or school just isn’t for them. If everyone is a puzzle piece that fits into society in a certain way, our edges come back frayed and worn. Everything doesn’t go back together quite right. But what I want to tell everyone who wants to go back is this: It’s not what we did that you miss, it’s the people you served next to. Just like now, as we’re scattered all over the country, bringing the men of second platoon together for another tour remains an impossible task. If it wasn’t, I doubt I could resist the opportunity. I know what the miners know – those terrible days were the best days because of who was with them in the dark.

Peculiar things happen when you catch up with a guy from the platoon. Voices change, conversation becomes hurried and the wall between thoughts and speech, usually reserved for polite society, crumbles to dust. The social experiment of a platoon stuffed together for fifteen continuous months of combat breeds words, phrases and nicknames that are buried when those men finally disperse, only to be resurrected later during brief reunions. If the men of second platoon spoke as they did in the filthy outposts of Baqubah, most would be divorced and none would be employed. Reintegrating into society means you must leave those words, phrases and tones behind, mostly for the reason that civilians would simply not understand them. When old friends get together, those words come tumbling out from the deepest recesses of the mind.

When civilians ask me what I miss most about the Army, I always tell them it’s the people. Many are one of a kind and others are destined to be friends for life. Given a few years separation between the end of a military career and the return to civilian life, it becomes easy to romanticize the way things used to be. Even sheer moments of terror and unimaginable brutality seem tolerable in retrospect because of the men to the left and right. Love is a difficult emotion to conceptualize, and I did not understand it until I saw guys sharing their last swallows of water or offering to carry some of the heavy load for a struggling friend. Once we got home and everyone went their separate ways, or stayed for another tour, that support system fell apart. It was worth the agony of war to experience that kind of commitment.

It came as no surprise to hear that the Chilean miners almost immediately began to have what I call adversity withdrawal. In the two months they were underground, everything in their lives – their wives and girlfriends, their homes, their paychecks- melted away the moment they were trapped. Their only concern was survival, and they began to live moment to moment with an outcome far from certain. Undoubtedly, the bonds they forged deep underground helped them get through what must have been a truly horrifying experience. One sentence from a recent report nearly knocked me out of my seat:

“What we’re seeing is the miners are almost longing to be in that group together.”

For the third time this year, I spent quality time with Dodo, one of my best friends from the platoon. We always talk about work and girlfriends and who is up to what, but the topic always drifts towards the Army and Iraq, as if the conversation is a compass that points to what is really on our minds. I have discovered that several guys from the platoon have thought about joining up again. Going back to a job or the unemployment line or school just isn’t for them. If everyone is a puzzle piece that fits into society in a certain way, our edges come back frayed and worn. Everything doesn’t go back together quite right. But what I want to tell everyone who wants to go back is this: It’s not what we did that you miss, it’s the people you served next to. Just like now, as we’re scattered all over the country, bringing the men of second platoon together for another tour remains an impossible task. If it wasn’t, I doubt I could resist the opportunity. I know what the miners know – those terrible days were the best days because of who was with them in the dark.