Since the inception of the Stupid Shit editions that find themselves scattered across this blog, I had planned on a Stupid Shit of The Year, listing all the candidates and having some sort of vote on what you, the most faithful of readers felt was the most inane and infuriating of all entries. Up to that point, they were all unexplainable rifts in common sense. All of it was maddening but we took it in stride as part of our job. It was so close to that moment, but before the end of the year, a single second stood tantamount to the stupidest shit I’ve ever witnessed.

On Christmas Day on the streets of Baghdad, we were greeted with student protests, hundreds marching throughout the city shouting anti American slogans as the mosque loudspeakers boomed with harsh rhetoric. Atop rooftops we could see them massing, and eventually we were called down to street level to deal with possible rioting. We met face to face with the protesters, both sides debating the consequences of dealing the first blow. I took a knee next to my compatriot and loaded a soft tipped grenade into my launcher to dissuade the more restless in the crowd; one tap to the chest and you’d be sent hurling into the mud. After a hasty Mexican standoff, we loaded up to head back to our base as the crowd cheered an apparent victory. Down the road, more were waiting for us with burning trash used as barricades to stop us in our tracks while rocks and chunks of concrete rained down on the hatches from rooftops. Grinches were definitely out in full force, but everyone made it back safe.

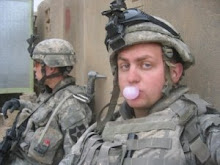

Wait, is this the line for PS3?

The stage was set for the next day, the day it came together for me. The day I finally understand how this conflict is being fought, in all the wrong ways most dangerous to those who are doing the fighting, protecting the very people at the top who are not. The day I was shot at for the first time in almost six months to the day I deployed, and the first time I ever shot back. Our mission was hazy and vague; sit outside the volatile section of Sadr City and wait for the enemy to come to us. We lazily scanned rooftops watching for machine gunners and snipers. I had just come from the stairwell where I was watching for anyone try to ambush us, but met only women and friendly kids. I was there but a few minutes when the horizon shook with a fierce sound of fire: clack-clack-clack-clack-clack. It was not the sound of our own. Five men including me pinpointed the fire coming from a rooftop in the Sadr City limits, and engaged. He soon disappeared, maybe dead, maybe not. We continued to lay down fire until I was told to stop. In between shots I attempted to mark the target with smoke grenades but both failed to perform. I intricately repeated through my head what happened for the next few minutes, coming up with all kinds of ‘what if’ scenarios. I’m sure it’s normal.

The rules of engagement were designed to protect the innocent and to prevent madmen from becoming murderers under the guise of defense. It states you must only fire at targets that are a direct threat to you. But, you can also shoot when you feel your life is threatened. In conventional war, this must have been simple to follow. You have two opposing sides, using conventional tactics with the wear of recognized uniforms. It wasn’t hard determining who was on your side and who wasn’t. There was honor and respect between foes. Flashes of history show us this. On Christmas Day in 1914, British and German troops ceased fighting for that day to trade cigarettes, coffee and stories. They played soccer in no man’s land, the ground where hundreds of thousands perished on both sides during futile advances. In Bastogne during WWII, again in the spirit of Christmas, German and American troops exchanged lines of Silent Night from their respective lines. They too continued one of the bloodiest battles of the war the next morning.

Welcome to twenty first century warfare.

American soldiers are breaking their backs to be the good guys in this war, to represent our leaders and the public we serve. We’re trying to remove the shame of Abu Ghraib and soldiers who raped and murdered Iraqi girls. When clearing blocks, we cut locks and if necessary, kick doors off hinges to search for weapon caches. If the people are home, we give them a number to call so they can collect money for their damaged property. In WWII, troops cleared houses by throwing in grenades without checking to see if a family is huddled in the corner. A terrible thing could happen, but it’s a war after all. We now have paintball guns and non-lethal shotgun rounds. Do you think the enemy carries the same? Who is this really helping?

I told you all of that to tell you what else happened on the roof that day. Minutes after the firefight, all of us noticed a black sedan making the same rounds through alleys and side streets. Always stopping in the same spot, always backing up at the exact same distance. The driver along with a passenger in the front seat and back seat were concealing most of the frame behind a building, leaving only the right passenger door facing us. Insurgents have been known to use sniper rifles inside cars so they can make quick getaways in traffic. It’s something we all know and watch for. This car was using textbook actions in a moving sniper platform. Immediately my team leader called up to my squad leader, who too became suspicious. We all wanted to take a shot, at least in the trunk of the car to scare the driver off, who was more than 300 meters away. Instinct was prevailing. We kept our sights on the car, which disappeared only to come back to the same spot and repeat his routine. It’s been 20 minutes. The call to take the shot went higher up the chain, the story getting more distorted and twisted the more ways it was interpreted to a higher ranking officer, all who weren’t there with us. It came back down the chain: don’t take the shot. It became a political decision; what if we were wrong? That's a lot of paperwork. We all cursed whoever kicked it back. I thought out loud about shooting and defending my actions later. I was told not to again. We watched the car leave, only to round the corner one more time and stop. He backs up, once again exposing his rear right window in a perfect line of sight to our rooftop. Once again the request to open fire was denied.

The window comes down.

Children in the alleyway scatter in all directions.

A flash of light fills the open window.

PSSSSSHEW.

When bullets fly near you, they pop as they make sonic boomlets. Closer still, they make hissing noises like a rattlesnake slithering past you faster than the speed of sound. In a split second, you realize you’re not dead. Your second thought is, “where did it go?” I looked over to my team leader five feet to my right, shouting obscenities and holding his ear. I thought he had been shot. Quickly I realize the bullet came so close to his head that it damaged his hearing for a moment. My ears were ringing as well. As for the sniper, he got away. The time from the shot to when the car moved into the alley was less than a second. Kill or no kill, the sniper made it back to his family that night. He used against us our most honorable and foolhardy trait: our adherence to the rules. And we, the most powerful force the earth has known, have been effectively neutered.

So dreadful the thought of civilian casualties that rules of engagement get more constricting by the day. Americans and the rest of the world are unwavered at the sight of our boys coming home in body bags, but Iraqi deaths are too much to handle. They call for tougher rules, for more discipline. They want us to accomplish our mission but can’t stomach the fact it could result in civilian deaths. Now chew on this: what if we shot at that car, and it turned out to be nothing? What if it ricocheted and killed a little girl? Would we still be right? The answer is yes. It’s unsettling to think in such cold terms, but you, the American public that cover your SUVs in yellow ribbons with the most shameful definition of support that has ever been conceived, burden those in the military with all the responsibility and guilt of a war that couldn’t exist without the Senate you elected. You thank us for protecting your freedom, then with infinite ignorance, look the other way while the death toll mounts, largely because of limits imposed by the government, all the way down the chain of command to the individual on the rooftop. It’s perpetuated by the vocal citizens who demand we keep civilian casualties down at all costs, and that reverberates through the halls of Washington. It trickles down to the senior officers who have careers to protect, where accountability comes back on them. The ones who make the call not to shoot at the alleged sniper in a car somewhere on a cold street in Baghdad.

Before I left for the Army, my father told me an old adage I should have kept dear: “I’d rather be judged by twelve than carried by six.” It needs no explanation. Those who were on the rooftop agreed that the next time we get that gut feeling, we’re acting on it. Even if the world says it’s a crime. I’ll leave this with another quote, from famed journalist Dan Rather:

In a constitutional republic such as ours, you simply cannot sustain warfare without the people at large understanding why we fight, how we fight, and have a sense of accountability to the very top.

The next time, I’m shooting. I might be judged by twelve, but it beats the alternative.

AH