A few weeks ago I had the pleasure of hearing Tim O'Brien speak at Texas State University about the art of writing. He read from a recent magazine article and entertained a few questions. During his book signing I presented a copy of "The Things They Carried" that I literally did carry in Iraq. Its edges were torn and bent, the pages browned by dust and sand. I brought an edited copy of an old favorite entry on here, The Thing I Carried, thanked him for the reading, and handed over the copy. The version I gave him is reproduced here. Enjoy.

The Thing I Carried

Out of the Army and into school. That was the simple plan that many of us adopted before we deployed in the summer of 2006. In between crusty Army lifers were shortimers, soldiers approaching the twilight of their enlistment. For some, two deployments to Iraq were enough for a lifetime. Others made plans to get out before desert boots touched foreign sand.

When it came time to sort out, pack and load equipment, a lot of guys were buying their own gear to take with them. Any junior enlisted soldier knows the issued equipment is inferior to anything you can go out and buy for yourself. The assault pack was one of those things. Its dimensions fit the criteria of a regular backpack, save for the digital camouflage and extra utility pouches. The zippers are what you come to expect from the Army’s lowest bidding contractor. They were difficult to shut and snagged easily on the sides. The compartments were more suited for textbooks and notepads, not the instruments of war that infantrymen would need to carry. Knives, batteries, carabiners, socks, water, rations, folded up letters. The things I needed to carry grew larger than my capacity to carry them.

Jesse hooked our whole squad up with aftermarket equipment weeks before we boarded an eastbound plane. His father’s company sponsored us with enough money to buy essentials like magazine and utility pouches, vests and grenade bandoleers. He budgeted himself enough money to buy a brand new assault pack. He didn't need the one from his first deployment, so he passed it down to me.

"You can use it the whole time we’re over there, but you have to give it back to me," he said.

"But if you decide to reenlist, you can keep it."

"You'll definitely be getting it back," I replied.

The assault pack was worn out after one deployment but still held together fairly well. The bottom corner was tearing and foam cushioning was exposed and damaged. Jesse had written his Hawaiian name, Keawe, in thick black lettering on the front. I sewed on a nametape across the hand drawn letters. On the bottom pouch I wrote in small print, 24 Nov 2007, the day I was getting out of the Army. It was below a message Jesse had written, perhaps before his first deployment - For those who would NOT serve

***

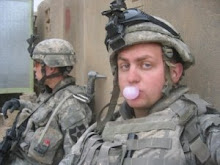

It was becoming a routine to leave our base outside of Baghdad and spend up to a week in smaller bases sprinkled around the heart of the city. The capital proved to be an underwhelming backdrop to a mission that was starting to grow more frustrating as the days melted together into a pool of hazy memories. Snipers took pot shots as we cleared swaths of neighborhoods, only to reclear them later. For every time we met the enemy face to face we returned fire ten times, mostly at nothing. The action was so dismal that assault packs held things to combat boredom instead of insurgents. Mp3 players, books, movies, chess sets, snacks. I carried all of Lauren's letters with me so I could read them over and over in the middle of the night. The rain had stained the notebook paper blue and red.

By the time we got to Baqubah, Jesse had moved to another platoon. I saw him less than before but he never stopped asking me when I was going to get a girlfriend. On the day I went on leave, Josh mentioned that a young college student named Lauren was writing to me from Seattle. My platoon was getting their gear on and heading out to surveil possible arms traffickers, but I stayed behind to watch them as I told Jesse the unlikely story of my budding romance with a girl thousands of miles away.

"Damn dude, good luck with that shit," he said.

In case my platoon got the call to move out while I was gone, my assault pack and rucksack were left behind and packed neatly on my mattress. I headed to the flightline and took the next chopper out to Baghdad. My best friend and I decided traveling around in Europe by train would be easier than going home to sleep in our old beds. In many ways, we had grown out of them.

***

As I made the long trek back to the desert from the fertile landscapes of Italy and Germany, Jesse was on another plane bound for the States. He lay inside a flag draped coffin aboard a transport plane among others killed in theater. He had spent a total of twenty-two months in combat before a sniper found his brown eyes through a scope.

When I walked back into the platoon tent for the first time in three weeks, it was dark and completely empty except for Josh. He stayed back from missions after sustaining a concussion from a personnel mine. He didn’t say anything at first, but motioned for me to sit on his bed. He dug out a copy of Jesse’s memorial program and stuffed it into my hands. I looked over to my bunk to see Jesse’s assault pack still on my bed. Keawe playfully stood out from behind the nametape.

***

From the moment our feet touched American soil for the first time in fifteen months, the assault pack became a backpack. A year later I was in school with the same sand colored bag at my feet . I traded grenades for pens and ammunition magazines for textbooks. Around campus I can spot other veterans of the wars easily; they still carry their assault packs too. They may have moved on to get an education, but they have chosen to carry part of their former lives with them. The burden of readjustment and the malignant feeling of wanting to be back there weigh heavily on their shoulders. The things they carry in their assault packs weigh more than a thousand books.

Somewhere in the dense palm groves of the Diyala River Valley is my true self. I left behind a boisterous and outspoken personality for a muted and introverted existence in the classroom. I volunteer answers enough to get by with a passing grade for class participation, but I can only yield the topics of Iraq and war to the daftly opinionated classmates that surround me like a pack of oblivious wolves. I was raised in the same era as my peers, but I did not grow up with them. The chasm between us only grows larger when I want to speak up about war, but cannot find the words.

For those who would NOT serve – the words fade a little more each day. I secretly wish that another veteran will read it, see the dangling 550 cord hanging from one of the buckles and deliver the standard icebreaking question, "So, where were you at?" At least then I could be myself with someone that carries the same load on their shoulders.

The Thing I Carried

Out of the Army and into school. That was the simple plan that many of us adopted before we deployed in the summer of 2006. In between crusty Army lifers were shortimers, soldiers approaching the twilight of their enlistment. For some, two deployments to Iraq were enough for a lifetime. Others made plans to get out before desert boots touched foreign sand.

When it came time to sort out, pack and load equipment, a lot of guys were buying their own gear to take with them. Any junior enlisted soldier knows the issued equipment is inferior to anything you can go out and buy for yourself. The assault pack was one of those things. Its dimensions fit the criteria of a regular backpack, save for the digital camouflage and extra utility pouches. The zippers are what you come to expect from the Army’s lowest bidding contractor. They were difficult to shut and snagged easily on the sides. The compartments were more suited for textbooks and notepads, not the instruments of war that infantrymen would need to carry. Knives, batteries, carabiners, socks, water, rations, folded up letters. The things I needed to carry grew larger than my capacity to carry them.

Jesse hooked our whole squad up with aftermarket equipment weeks before we boarded an eastbound plane. His father’s company sponsored us with enough money to buy essentials like magazine and utility pouches, vests and grenade bandoleers. He budgeted himself enough money to buy a brand new assault pack. He didn't need the one from his first deployment, so he passed it down to me.

"You can use it the whole time we’re over there, but you have to give it back to me," he said.

"But if you decide to reenlist, you can keep it."

"You'll definitely be getting it back," I replied.

The assault pack was worn out after one deployment but still held together fairly well. The bottom corner was tearing and foam cushioning was exposed and damaged. Jesse had written his Hawaiian name, Keawe, in thick black lettering on the front. I sewed on a nametape across the hand drawn letters. On the bottom pouch I wrote in small print, 24 Nov 2007, the day I was getting out of the Army. It was below a message Jesse had written, perhaps before his first deployment - For those who would NOT serve

***

It was becoming a routine to leave our base outside of Baghdad and spend up to a week in smaller bases sprinkled around the heart of the city. The capital proved to be an underwhelming backdrop to a mission that was starting to grow more frustrating as the days melted together into a pool of hazy memories. Snipers took pot shots as we cleared swaths of neighborhoods, only to reclear them later. For every time we met the enemy face to face we returned fire ten times, mostly at nothing. The action was so dismal that assault packs held things to combat boredom instead of insurgents. Mp3 players, books, movies, chess sets, snacks. I carried all of Lauren's letters with me so I could read them over and over in the middle of the night. The rain had stained the notebook paper blue and red.

By the time we got to Baqubah, Jesse had moved to another platoon. I saw him less than before but he never stopped asking me when I was going to get a girlfriend. On the day I went on leave, Josh mentioned that a young college student named Lauren was writing to me from Seattle. My platoon was getting their gear on and heading out to surveil possible arms traffickers, but I stayed behind to watch them as I told Jesse the unlikely story of my budding romance with a girl thousands of miles away.

"Damn dude, good luck with that shit," he said.

In case my platoon got the call to move out while I was gone, my assault pack and rucksack were left behind and packed neatly on my mattress. I headed to the flightline and took the next chopper out to Baghdad. My best friend and I decided traveling around in Europe by train would be easier than going home to sleep in our old beds. In many ways, we had grown out of them.

***

As I made the long trek back to the desert from the fertile landscapes of Italy and Germany, Jesse was on another plane bound for the States. He lay inside a flag draped coffin aboard a transport plane among others killed in theater. He had spent a total of twenty-two months in combat before a sniper found his brown eyes through a scope.

When I walked back into the platoon tent for the first time in three weeks, it was dark and completely empty except for Josh. He stayed back from missions after sustaining a concussion from a personnel mine. He didn’t say anything at first, but motioned for me to sit on his bed. He dug out a copy of Jesse’s memorial program and stuffed it into my hands. I looked over to my bunk to see Jesse’s assault pack still on my bed. Keawe playfully stood out from behind the nametape.

***

From the moment our feet touched American soil for the first time in fifteen months, the assault pack became a backpack. A year later I was in school with the same sand colored bag at my feet . I traded grenades for pens and ammunition magazines for textbooks. Around campus I can spot other veterans of the wars easily; they still carry their assault packs too. They may have moved on to get an education, but they have chosen to carry part of their former lives with them. The burden of readjustment and the malignant feeling of wanting to be back there weigh heavily on their shoulders. The things they carry in their assault packs weigh more than a thousand books.

Somewhere in the dense palm groves of the Diyala River Valley is my true self. I left behind a boisterous and outspoken personality for a muted and introverted existence in the classroom. I volunteer answers enough to get by with a passing grade for class participation, but I can only yield the topics of Iraq and war to the daftly opinionated classmates that surround me like a pack of oblivious wolves. I was raised in the same era as my peers, but I did not grow up with them. The chasm between us only grows larger when I want to speak up about war, but cannot find the words.

For those who would NOT serve – the words fade a little more each day. I secretly wish that another veteran will read it, see the dangling 550 cord hanging from one of the buckles and deliver the standard icebreaking question, "So, where were you at?" At least then I could be myself with someone that carries the same load on their shoulders.